המאמר השישי בפרויקט Sivi קוראת צ’וסר

Please scroll down for an English review.

בין שלל הדמויות בפרולוג הכללי של צ’וסר, הנזיר הקבצן הוא אחד המופלאים. לא בגלל קדושתו, אלא בזכות יכולתו להפוך אותה לעסק משתלם. הוא איש דת עם רישיון מיוחד מהמסדר שלו, “לשאת ולתת” בתחומו. בפועל, זהו זיכיון דתי לכל דבר: אזור בלעדי לקבצנות מתוחכמת, עם מיתוג, לקוחות חוזרים ויחסי ציבור.

מבחינה היסטורית, צ’וסר מצביע על קרע עמוק בכנסייה: בניגוד לכמרים המקומיים שהיו כפופים לבישופות שלהם, הנזירים הקבצנים קיבלו את סמכותם ישירות מהאפיפיור. המשמעות היא שהוברט הוא “פרילאנסר דתי” שחותר תחת המבנה הכלכלי והקהילתי של הכנסייה. הוא לא רק גונב את הכנסותיו של הכומר המקומי; הוא מפריט את מושג הכפרה (Penance) והופך אותו למוצר מדף.

“מרשה לפשוט ידו, כולו הדרות.”

כבר מהשורה הראשונה צ’וסר צוחק על דמות הנזיר הקבצן. זה לא נזיר, זה נציג מכירות אלוהי, שיודע היטב שברכה מאלוהים ניתנת רק עם קבלה.

“החזיר איש בתשובה בלב שלם, כשליבו אמר: זה ישלם.

כי לנזיר אם איש נותן תשורה – משמע שחטאתו כבר נתכפרה.”

כך הופכת התשובה לעסקת חליפין קרה. אין צורך בחרטה פנימית או בתיקון מוסרי; די בתשלום נאות כדי “למחוק” את החטא. הכיס של הוברט מתמלא, והמצפון של החוטא נרגע, הפרטה מושלמת של הגאולה.

והוא גם יודע לעבוד בשטח:

“הכיר כל בית מרזח בכל עיר,

מוזגים וגם מוזגות היטיב לדעת יותר משידע מוכי צרעת.”

זהו משפט גאוני: במקום לטפל במצורעים, אותם שנואי נפש שהנצרות אמורה לרפא בחמלה, הוא בוחר ב”נטוורקינג” בבתי המרזח. החמלה נדחקת מפני ההזדמנות העסקית.

השיא מגיע במפגש עם האלמנה שאין לה אפילו פת בסל. גם לה הוא מוצא פתרון רוחני־מסחרי:

“הנעים לה in principio מסולסל, עד לא בחוסר כל שלחה אותו.

הכנסתו עלתה על משכורתו.”

שורה אחת, ומולנו נחשף המנגנון: לטינית מעודנת (“In principio”), מעט מוזיקה, מעט הילה של קדושה, ויציאה עם המטבע האחרון שלה. שלו, כמובן.

✧ פריבילגיה ונהנתנות: הקדושה שמריחה מבושם

צ’וסר בונה את הוברט כדמות של שפע ונהנתנות. הוא אינו חי חיי סיגוף, אלא חיי נוחות מוארים.

“כחבצת צוארו צחור הוא.”

הצוואר הלבן כחבצלת (fleur-de-lis) איננו רק עדות לכך שאינו עובד תחת השמש; אפשר לקרוא בו גם מסיכה. טוהר מצוחצח מדי, נקי מדי, כזה שמריח יותר כמו הצגה מאשר כמו ענווה. צוואר של אדם שלא נשא בעול המוסרי של תפקידו, או לפחות לא שילם עליו מחיר.

גלימתו אינה גלימת נזיר עני:

היא יפה, נקייה, כמעט משיית, כשל “מאסטר” או גביר.

הוא דמות דתית שנראית כמו אציל.

והקול שלו מוכר לא רק סליחה, אלא גם אושר:

“קולו, אין עוררין, כל לב הרטיט.

היטיב לשיר, פרט עלי גיתית,

בסלסולי בלדות.”

הנזיר הקבצן מוכר הנאה: שמחת חיים עטופה בשפה של קדושה. הוא הופך את הסגפנות למוצר מפנק, ובכך חושף את הפער בין האידיאל הדתי למציאות החומרית של הכמורה.

✧ קשרי הון ושלטון: הנזיר של האליטות

זהו איננו “קבצן רחוב” אלא שליח דת עם רישיון מוסדי, וגב שמגיע עד לרומא.

“אהוב היה מאוד ומקורב

אל אצילי הכפר שבתחומיו

ואל נשות העיר הנכבדות.”

זה לא שדה של חמלה. זה שדה של קשרים. הוברט פועל בתוך נטוורקינג עם בעלי הון, יוצר לעצמו מועדון VIP של קדושה. כל סיכה או סכין קטנה שהוא מקבל מהנשים הנכבדות אינן “נדבה”, אלא מנגנון לשימור נאמנות, גרסה מוקדמת של לקוח מועדף.

✧ שם פרטי כשיא החשיפה

צ’וסר מסיים את הקטע כמעט כבדרך אגב:

“והוברט שם אישנו הקבצן.”

הענקת השם בסוף היא מכה ספרותית. הוא נותן שם לשחיתות; הוברט הוא כבר לא סמל מופשט, הוא אדם עם פנים, עם שם שאפשר לזכור. מכאן ברור: הצביעות הדתית איננה תופעה, היא מקצוע.

והוא מקצוע של תקופה. הוברט הוא דמות חיה מאנגליה של ריצ’רד השני, עידן שבו מסדרי הקבצנים צברו כוח כלכלי, והמתח בין הכמרים המקומיים לנזירים הקבצנים הגיע לשיאו. האמונה התחילה להישמע כמו שירות לקוחות, והכפרה כמו עסקה.

צ’וסר כותב אותו מתוך הבנה צינית: האדם תמיד ימצא דרך לגאול את נשמתו, גם אם זה עולה לו קצת כסף.

🕯️דמות קדושה בעולם של שירות לקוחות

הנזיר הקבצן של צ’וסר הוא מראה מושלמת לעידן שבו האמונה הפכה לשירות לקוחות,

והגאולה לעסק מניב.

“והוברט שם אישנו הקבצן.”, אבל כולנו יודעים איך קוראים לו גם היום.

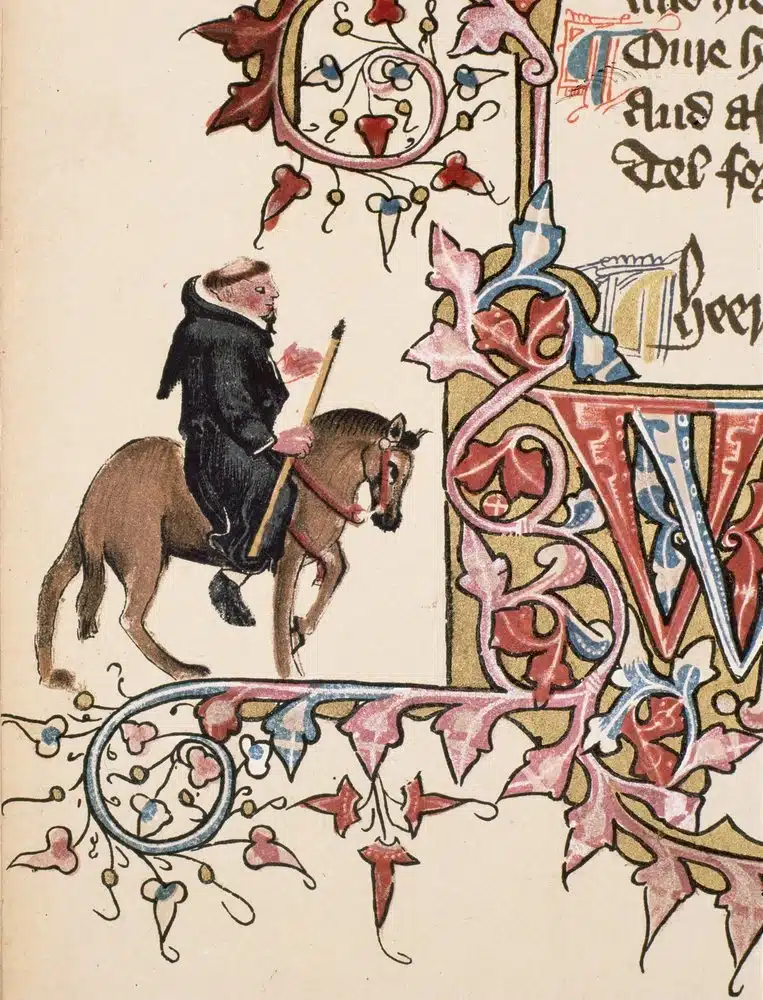

The Friar – Hubert, the Saint of Entrepreneurship

The Sixth Essay in the series Sivi Reads The Canterbury Tales

Among the many figures in Chaucer's General Prologue, the Friar is one of the most striking, not because of his holiness, but because of his ability to turn holiness into a profitable enterprise. He is a man of the Church with a special license from his order "to negotiate" within his territory. In practice, this is a religious franchise in every sense: an exclusive zone for sophisticated begging, complete with branding, repeat customers, and public relations.

Historically, Chaucer is pointing to a deep rupture within the medieval Church. Unlike parish priests, who were subordinate to their local bishoprics, the mendicant friars received their authority directly from the Pope. The implication is clear: Hubert is a religious freelancer who undermines the Church's economic and communal structure from within. He does not merely divert income from the local priest; he privatizes penance itself and turns absolution into a retail product.

"Licensed to beg, full of elegance and grace."

From the very first line, Chaucer is already smiling. This is not a monk; this is a divine sales representative, fully aware that God's blessing comes only with a receipt.

"He brought men to repentance gladly,

For when a man had paid, his heart was ready.

If someone gave the friar a gift,

His sin, by that very act, was already absolved."

Repentance becomes a cold transaction. There is no need for inner remorse or moral repair; a suitable payment is enough to erase the sin. Hubert's purse fills, and the sinner's conscience is soothed—a perfect privatization of salvation.

He also knows how to work the field:

"He knew every tavern in every town,

Every innkeeper and barmaid better

Than he knew the lepers."

It is a devastating line. Instead of tending to lepers, those most despised and in need of Christian compassion, he chooses networking in taverns. Mercy is displaced by opportunity.

The climax comes with the encounter with a widow who has nothing to her name. Even for her, he offers a spiritual solution with a price tag:

"He sang to her a soft In principio,

Until she gave her last coin.

His income surpassed his fixed salary."

In a single stroke, Chaucer exposes an economic mechanism of paid redemption. Hubert sings refined Latin, sells her the illusion of absolution, and walks away with her last money—a predatory system of grace.

✧ Privilege and Pleasure: Holiness That Smells of Perfume

Chaucer constructs Hubert not only as an economic manipulator but also as a figure of abundance and indulgence. He does not live a life of asceticism, but one of comfort and polish.

"Merry and gracious, licensed to beg."

Then comes one of the sharpest images in the Prologue:

"His neck was white as a lily."

This lily-white neck is not simply proof that he does not labor under the sun; it signals moral softness. A cosmetic purity masking corruption. The neck of a man who has never carried the ethical weight of his office. His robe is not that of a poor friar; it is clean, elegant, almost aristocratic.

His voice does not sell forgiveness alone, but pleasure:

"His voice stirred every heart,

He sang and played the harp,

A master of ballads and melodies."

The Friar sells joy. Pleasure wrapped in sacred language. He transforms asceticism into a luxury experience, exposing the gulf between religious ideal and clerical reality.

✧ Capital and Power: The Friar of the Elite

This is no street beggar. He is an institutional agent, armed with papal authority.

"He was well loved and intimate

With the country gentry

And with the respectable women of the town."

This is not a field of compassion, but of networking. He cultivates relationships with the wealthy, building a VIP circle of sanctity. Every pin, knife, or trinket he receives from these women is not charity but a mechanism of loyalty—early client retention.

This is clerical power as a business model. Faith operates as an elite service.

✧ A Name as Final Exposure

Chaucer ends almost casually:

"And Hubert was the friar's name."

Naming him at the end is a literary blow. Corruption is given a proper name: no longer an abstract vice, but a recognizable professional identity. Hypocrisy is not an accident; it is a career.

Hubert is not a caricature. He is a living figure of Richard II's England, a time when mendicant orders amassed economic power, shame evaporated, and tensions between friars and parish priests reached a breaking point. Faith became customer service. Redemption became revenue.

Chaucer writes him without hatred, but with cold clarity. Humans will always find a way to redeem their souls, even if it costs them a little money.

"And Hubert was the friar's name."

And we all know what his name would be today.

לגלות עוד מהאתר Sivi's Books

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.