Please scroll down for an English review.

קראתי את "המלכה הלבנה" כמו שמתחילים סדרה טובה בלילה הלא נכון: פרק ועוד פרק, עד שקלטתי איפה גרגורי ערכה את המציאות. פיליפה גרגורי יודעת לכתוב. היא קולחת, ממכרת, ומגישה את מלחמות השושנים, תקופה שגם היסטוריונים מתקשים לעשות בה סדר, כדרמה פוליטית שאי אפשר להניח מהיד. אבל היא עושה את זה במחיר של אמת היסטורית, והקו הזה, אצלה, לא תמיד מסומן לקורא.

הקו עובר ברגע שבו היא מסדרת את הכאוס כאילו מעולם לא היה כאוס. מרגע שהיא בוחרת גיבורה אחת ומסדרת סביבה את העולם, היא גם בוחרת בשביל הקורא מה הוא יחשוב שהוא "יודע".

העלילה: הישרדות בתוך מכונת בשר

מלחמות השושנים, הן מאבק ירושה שבו האויב הוא לא צבא מעבר לים אלא בן משפחה, והנאמנות מחליפה צדדים כמו מעיל. זה אורובורוס פוליטי: שושלת שאוכלת את עצמה.

הסיפור הוא סיפור חייה של אליזבת וודוויל. היא מתחילה כאלמנה צעירה ממעמד האצולה הנמוך שצריכה להציל את עתיד ילדיה, ומוצאת את עצמה במפגש גורלי עם המלך אדוארד הרביעי. זה קורה בדיוק כשהקלחת המשפחתית רותחת: מאבק ירושה אלים ועקוב מדם בין שני ענפים של בית המלוכה: בית יורק (השושנה הלבנה) ובית לנקסטר (השושנה האדומה).

כשהשניים נישאים בסתר, הממלכה לא סתם "מתפוצצת" מזעם על האופי הרומנטי וחסר האחריות של המלך; נוצר משבר פוליטי אדיר. הנישואים נתפסו כעלבון צורב לאצולה הוותיקה. הקידום המטאורי והדורסני של משפחת וודוויל, משפחה שהחצר סימנה כזרים בלי משקל שושלתי, ערער את מוקדי הכוח הישנים והוציא אותם משיווי משקל.

משם הספר רץ על פני הבגידות המפורסמות של ווריק "עושה המלכים", שגילה שהמלך שייצר כבר לא סר למרותו, התמרונים של ג'ורג' דוכס קלרנס שתמיד חיפש את הצד המנצח, ועד לבור השחור של היעלמות הנסיכים במגדל ועלייתם של ריצ'רד השלישי ובית טיודור. אצל גרגורי, אליזבת הופכת למלכה בעולם שבו הכתר הוא פחות תכשיט ויותר מטרה על הגב, וההישרדות שלה תלויה במידת היכולת שלה להפוך את השמועות נגדה לנשק.

המנגנון: כישוף ככלי נשק פוליטי

גרגורי עושה שימוש נרחב במוטיב הכישוף. אליזבת ואמה ז'אקטה מוצגות כמי שמזמנות סערות וקוראות סימנים. כספרות זה עובד, כל עוד הכישוף נשאר שמועה: כלי שמכשיר מיזוגניה, ומסביר לקהל למה "ברור" שהמלך נשלט ולמה המלכה מסוכנת.

אבל ברגע שהטקסט משתמש בכישוף כפתרון בפועל, סערה שמגיעה בדיוק בזמן כדי לעצור צבא, זה כבר לא ניתוח של פחד. זה חילוץ עלילתי. לא נשק פוליטי, אלא דאוס אקס מכינה.

ואז חוזרים לנוחות הגדולה של התקופה וגם של הרומן: הרבה יותר קל לייחס תבוסה ל"כוחות אפלים" מאשר לטעות, אינטרס, או פשוט כאוס.

איפה זה חורק? האנכרוניזם של הידע

הבעיה המרכזית שלי עם הספר, במיוחד בשליש האחרון, היא הנטייה של גרגורי לתת לדמויות מודעות היסטורית שאינה שייכת לתקופה. הדמויות פועלות ומדברות כאילו הן קראו את תקציר ההיסטוריה במאה ה-21. כשאליזבת וודוויל מנהלת דיאלוגים על "גברים בעלי שררה שקובעים מהו החוק", זה נשמע מודרני מדי. גרגורי מעבה מניעים פסיכולוגיים ורגשיים במקומות שבהם התקופה דורשת דווקא דיוק וצניעות ראייתית.

והדבר שהכי צרם לי שזו גם סתירה פנימית. גרגורי נותנת לאליזבת ולבתה לקלל את רוצח הנסיכים, ובאותה נשימה מסדרת את הנישואים של הבת להנרי טיודור, שהטקסט עצמו רומז שהוא הרוצח. זה לא 'מורכב'. זה טריק עלילתי. את לא יכולה לדרוש מהקורא להאמין בכישוף כמוסר, ואז להחליף הילוך כשצריך לחבר את ההיסטוריה לסוף הטיודורי ה"נכון".

היא בונה קונספירציות שלמות: כמו הרעיון שאליזבת הבריחה את בנה הצעיר לגלות והחליפה אותו בכפיל, או שריצ'רד השלישי ואליזבת מיורק (בתה של אליזבת וודוויל) ניהלו רומן. דברים שאין להם ביסוס במקורות, אבל הם משרתים את הצורך שלה בוודאות עלילתית נוחה.

השורה התחתונה: סיפור טוב מול אמת מלוכלכת

גרגורי לא כותבת היסטוריה; היא כותבת פנטזיה פוליטית עם רישיון להשתמש בשמות אמיתיים. היא מצליחה להעביר את החרדה התמידית של התקופה, את העובדה ש"אין קדוש באנגליה" ושהכול עומד למכירה, מכבוד ועד זכות מקלט במנזר.

זה ספר מצוין למי שרוצה תככים, קצב, ודמויות נשיות שפועלות בתוך עולם גברי בלי להתנצל, לא כדי לשנות את המערכת אלא כדי לשרוד אותה ולנצל את הסדקים שלה. אבל מי שמחפש להבין באמת מה קרה בין השנים 1464 ל- 1485, צריך לזכור שגרגורי מוכרת לנו ודאות במקום שבו ההיסטוריה השאירה רק סימני שאלה. היא לא מלמדת מה היה. היא מלמדת כמה מהר אנחנו קונים סדר, כשהאמת נראית כמו בלגן.

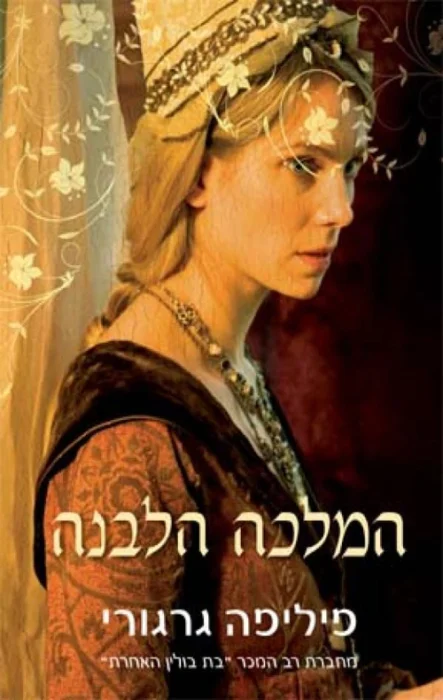

המלכה הלבנה/ פליפה גרגורי

אופוס, 2010, 448 עמודים

דירוג SIVI –

איכות אודיו –

The Plantagenet and Tudor Novels #2

I read The White Queen the way you start a good series on the wrong night: one chapter, then another, until I finally noticed where Gregory had edited reality. Philippa Gregory can write. She’s fluent, addictive, and she serves the Wars of the Roses, a period even historians struggle to keep tidy, as political drama you can’t put down. But she does it at the expense of historical truth, and with her, that line is not always clearly marked for the reader.

The line appears the moment she arranges chaos as if it were never chaos. The second she chooses one heroine and builds the world around her, she also chooses what the reader will think they “know.”

The plot: Survival inside a meat grinder

The Wars of the Roses are a succession struggle in which the enemy isn’t an army across the sea but a relative, and loyalties shift like coats—a political ouroboros: a dynasty eating itself.

This is the life story of Elizabeth Woodville. She begins as a young widow of relatively modest rank who has to secure her children’s future, and she finds herself in a fateful encounter with King Edward IV. It happens precisely as the family cauldron boils: a violent, blood-soaked succession conflict between two branches of the royal house, York (the white rose) and Lancaster (the red).

When the two marry in secret, the kingdom doesn’t merely “explode” in outrage at the romance and irresponsibility of the king. A massive political crisis is born. The marriage is read as a slap in the face to the old aristocracy. The meteoric, abrasive rise of the Woodvilles, a family the court labels as outsiders without proper dynastic weight, destabilizes the old centers of power and throws them off balance.

From there, the novel races through Warwick “the Kingmaker,” who discovers that the king he manufactured no longer obeys him, the maneuvers of George, Duke of Clarence, always hunting for the winning side, and then into the black hole of the Princes in the Tower and the rise of Richard III and the Tudor house, in Gregory’s telling, Elizabeth becomes a queen in a world where a crown is less jewelry than a target on your back. Her survival depends on her ability to turn the rumors against her into weapons.

The mechanism: Witchcraft as a political weapon

Gregory leans hard on the witchcraft motif. Elizabeth and her mother, Jacquetta, are portrayed as women who summon storms and read signs. As fiction, it works as long as witchcraft remains a rumor: a tool that legitimizes misogyny, explaining why it’s “obvious” the king is bewitched and why the queen is dangerous.

But when the text uses witchcraft as an actual solution, a storm arriving at the exact right moment to stop an army, it stops being an analysis of fear and becomes a plot rescue. Not a political weapon, but a deus ex machina.

And then we return to the great comfort of the era, and of the novel: it’s far easier to blame defeat on “dark forces” than on mistakes, interests, or plain chaos.

Where it grinds: the anachronism of knowledge

My main issue with the book, especially in the last third, is Gregory’s tendency to give her characters historical awareness that doesn’t belong to their time. They act and speak as if they’ve read a twenty-first-century history summary. When Elizabeth Woodville delivers lines about “powerful men deciding what the law is,” it sounds too modern. Gregory thickens psychological and emotional motives in places where the period demands restraint and evidentiary humility.

What irritated me most is that it’s also an internal contradiction. Gregory lets Elizabeth and her daughter curse the presumed murderer of the princes, and in the same breath, she arranges the daughter’s marriage to Henry Tudor, while the text itself hints that he is the killer. That’s not “complex.” It’s a plot trick. You can’t ask the reader to believe in witchcraft as a moral mechanism, and then shift gears when you need to connect history to the “correct” Tudor ending.

She builds whole conspiracies, such as the idea that Elizabeth smuggled her younger son into exile and replaced him with a double, or that Richard III and Elizabeth of York (Elizabeth Woodville’s daughter) had an affair. These have no real grounding in sources, but they serve her need for convenient narrative certainty.

Bottom line: a good story versus the dirty truth

Gregory isn’t writing history. She’s writing political fantasy with a license to use real names. She does capture the constant anxiety of the period, the sense that “no one in England is holy” and that everything is for sale, from honor to sanctuary rights in a monastery.

It’s an excellent book for readers who want intrigue, pace, and women who operate inside a male world without apologizing, not to reform the system but to survive it and exploit its cracks. But anyone who wants to understand what happened between 1464 and 1485 truly should remember: Gregory sells certainty where history left only question marks. She doesn’t teach what was. She teaches how quickly we buy orders when truth looks like a mess.

לגלות עוד מהאתר Sivi's Books

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.