Please scroll down for an English review.

חורחה סמפרון לא שרד את המחנה כדי לחיות, וגם לא כדי לכתוב. הוא שרד, ובמשך שנים ארוכות לא ידע לשם מה.

הכתיבה או החיים איננו “ספר זיכרונות”, אלא ניסיון נואש להשיב את השפה מן האפר.

השאלה שאותה סמפרון שואל אינה “מה אירע”, אלא “מה נותר מן האדם לאחר שהשפה עצמה נשרפה”.

סמפרון, יליד מדריד, בן למשפחה אינטלקטואלית, קומוניסט, לוחם רזיסטנס, אסיר בבוכנוואלד, גולה בצרפת, סופר, תסריטאי ושר תרבות בספרד. אך בראש ובראשונה, הוא אדם שהמוות לא הרפה ממנו מעולם. הספר, שנכתב ארבעים שנה לאחר שחרורו, הוא התנגשות בין זיכרון לשפה, בין קיום לאסתטיקה, בין הצורך לשתוק לצורך לומר.

השחרור

"אין הם יכולים להבין, לא ממש, שלושת הקצינים האלה. צריך היה לספר להם על העשן: דחוס לעיתים, שחור כפיח בשמיים המשנים גוון. או לעיתים קל ואפור, כמעט אד, משייט לו כחפץ הרוחות מעל לאנשים החיים שנקבצו יחדיו – כמין אות לבאות, להתראות בקרוב.

עשן כמין תכריכים עצומים כשמיים, עשן שהוא העקבות האחרונים להסתלקותם, בגוף ובנפש, של ידידים, גוף ונפש."

ביום השחרור, דבר לא היה ברור. השמש, שזמן רב כל כך לא זרחה, הלמה את עיניו של סמפרון בעוצמה כזו שכמעט והסיטה את מבטו. האור שבא אחרי האפלה, נדמה לחרב; אין זה אור של חיים, אלא חושך שמתגלה מחדש.

החיים, למי ששרד את התופת, הפכו למחזה של מוות שאי אפשר להסבירו או לבטאו.

הקשר שבין המסמל למסומל ניתק והמילים אינן מתארות משהו בעולם הפיזי.

ביום השיחרור, הוא פגש את חיילי בנות הברית שבאו להציל אותם, והפער בין המציאות שהוא חווה לבין השפה, הולם בו במלוא העוצמה.

איך אפשר להסביר להם את מה שקרה? איך אפשר לשקף את הזוועה במילים בנאליות?

אין קשר בין המילים שמזגזגות בתודעה של מי שחווה את הזוועה, לבין המציאות הכמעט פסטורלית שהחיילים נתקלים בה.

העשן, שהפך לא רק למטאפורה של מוות, אלא לאייקון של כל מה שנשאר. העיניים המותשות של הניצולים במבט של ציפייה בלתי נגמרת, חיפוש אחרי מילה אחת שתהיה תואמת לאסון, למקום.

השפה מעניקה אשליה של שיתוף, אבל בעצם כל אחד כלוא בתוך החוויה הסובייקטיבית שלו.

"לא היו שם אנשים ששרדו, בצריף ההוא שב'מחנה הקטן'. העיניים הפקוחות לרווחה, הפעורות אל זוועת העולם, המבטים הפעורים, הבלתי חדירים, המאשימים – היו כולם עיניים כבויות, במטים מתים.

חלפנו, אלברט ואני, בגרון נשנק, בדממה הדביקה. בצעד קליל ככל הניתן. המוות פרש כאן את מלוא זנבו המרהיב, מפריח זיקוקין די נור קרחיים מכל העיניים הפקוחות אל תוהו העולם, על פני נוף התופת".

סמפרון הבין שהשחרור הוא לא נקודת סיום אלא התחלה. השחרור הוא לא באמת בריחה מהזוועה. נקודת המבט שלו, אינה סנטימנטלית. הוא לא מחפש נחמה, אלא מדייק את העיוות הקיומי שהשאיר המחנה בתודעה.

השיחרור אינו רגע הגאולה אלא תהלוכה אבסורדית של ניצולים שנעים בין גופות מתות, שנותרו עם עיניים פקוחות. זהו יום עצמאות במובנים רבים, אך כל פסיעה בו היא בין חיים ומוות, פארסה חגיגית שבה כל צעד מסמל את מחיר ההישרדות.

השפה שנשברה

המעבר מהחיים למחזה המוות שבר את סמפרון לא רק פיזית ונפשית, אלא גם לשונית. אחרי שהשחרור הותיר אותו חסר מילים, הוא מצא את עצמו עומד מול שפה שכבר לא יכלה לתאר את מה שעבר עליו.

כל גשר מילולי ל"אני" נרקב, והכתיבה לא יכלה להיות דבר שונה מההימלטות הפנימית מהמקום שבו נכלא.

" אגב, הניתן להעלות על הדעת את הפילוסופיה של היידגר נוצקת ללשון אחרת מלבד הגרמנית? כוונתי לומר, האם ניתן לחשוב על מעשה המישזר של עיקומים ועיוותים שביצע בלשון – מועתק לשפה אחרת שאינה גרמנית? איזה שפה תישא, מבלי להתפורר לאבק, דלפת של עמימויות, פסוודו אטימולוגיות מיוסרות ומייסרות מצלולים והדהודים רטוריים לעילא? אך כלום הגרמנית עצמה עמדה בסבל הזה? כלום לא הממה היידגר במכת מחץ שרק מקץ זמן רב התאושששה ממנה, לפחות בתחום המחקר הפילוסופי? "

השפה הגרמנית, שבעטיה נכתבו מסמכי ההשמדה, בגדה במציאות, קרסה מוסרית. היא שפה שנשלטה על ידי הרסנות קולקטיבית. האם היא בכלל מבטאת את ההוויה, כשהיא עצמה כל כך מקולקלת?

המילים לא רק שאיבדו את אמינותן; הן נהפכו לכלי שמעוות את העולם כצליל חלול וריק ממשמעות. כל מה ששרד בשפה היה אודים עשנים מנותקים מהזוועות שמתקיימות אך ורק פנימה של מי ששרד אותן.

סמפרון מעלה ספק לשוני אבל, אני קוראת אותו כמי שמעלה ספק מוסרי. הוא מעמיד על כרעי תרנגולת 200 שנות חשיבה פילוסופית: הוא אינו שואל אם בגרמנית ניתן לשחזר את "ההוויה", אלא מעלה ספק שבכלל ניתן לחשוב מחשבה אחת טהורה אחרי שהשפה חטאה.

בהיסטוריה של האפיסטמולוגיה הגרמנית, ישנו קו מחבר בין עימנואל קנט שגיבש את התנאים להכרה, הוסרל שהגדיר את מבנה התודעה והיידגר שהשליך מהתודעה להוויה.

אומנם, סמפרון מבקר את היידגר לא רק כמי ששרד את משטר הרשע, אלא כמי שלדבריו עיצב את הפילוסופיה מתוך לשון שלא שמה גבול לכאוס שמסביב. כאן, הוא גם מציב אתגר אמיתי ל- 200 שנות פילוסופיה גרמנית כאשר הוא טוען שבמבחן המציאות, כל ההגות הזו היא ניסוי מחשבתי שנשבר על מזח המציאות.

מה נותר מההוויה כאשר הגוף והנפש נרמסים? מה ערכה של תודעה כשהיא צופה באימה שאיננה ניתנת לתיאור?

חמישים שנים לאחר שויטגנשטיין פירסם את מסקנתו ב"טרקטט לוגי- פילוסופי" :

מה שאי אפשר לדבר עליו, על אודותיו יש לשתוק.

סמפרון עונה לו:

דווקא על מה שאי אפשר לדבר עליו, על אודותיו חייבים לדבר, גם אם זה בלתי אפשרי.

סמפרון כותב מתוך ההבנה שמילים לא יכולות לתאר את הזוועה, אך יש צורך בהן כמעשה של עדות, כמעשה שמתווך את הכאב לעולם החי, כמעשה של תחייה. הפער בין השפה לבין מה שהיא יכולה להעביר לא מונע ממנו להמשיך לכתוב.

זהו לב הספר: ניסיון להתגבר על השפה השבורה. לייצר מציאות חדשה שמדברת את מה שנמנע.

הכתיבה היא לא חיבור, היא פרידה; לא ניסיון "לתקן" את הזוועה, אלא לבחון איך אפשר לחיות בתוכה.

הכתיבה

סמפרון ידע שאין דרך אמיתית לכתוב על בוכנוואלד ולהישאר בחיים. זו לא הייתה תובנה מאוחרת, אלא ידיעה פנימית של מי שחווה את השתיקה כמנגנון הישרדות.

לכן הוא בחר בחיים. כלומר, בחר לשתוק.

שנים ארוכות לא כתב, לא דיבר, לא העיד. הוא חי, אבל מתוך הדחקה מכוונת, מתוך סירוב לחזור אל המקום ההוא.

הכתיבה או החיים איננו שם של דילמה רומנטית; זו הצהרה על בלתי האפשרי: אי־אפשר לשאת את שניהם גם יחד.

הכתיבה פירושה חזרה לבוכנוואלד, והחיים פירושם שכחה.

מי שינסה לשלב ביניהם, יישבר.

לעומתו, פרימו לוי כתב כדי לרפא את הפצע הפתוח. הוא האמין שהמילים ינקזו את המוגלה של הזיכרון, שסיפור מדויק עשוי להשיב לאדם את שלמותו.

אבל סמפרון ראה מה קרה לו, וחשש.

הוא הבין שכתיבה כזו, אם תיכתב באמת, תדרוש ממך למות שוב בכל פעם מחדש.

לכן הוא שתק.

לא מתוך פחד, אלא מתוך אינסטינקט של חיים.

השתיקה הפכה למעין מחסה זמני, אך גם לבית כלא. ככל שחלפו השנים, השתיקה עצמה החלה לכרסם אותו מבפנים. השתיקה הפכה לסממן של עוול לא מוסרי.

בסוף הוא נאלץ לכתוב; לא כי בחר בכתיבה, אלא כי השתיקה כבר הרגה אותו לאט מדי.

הכתיבה נולדה אצלו לא מתוך שאיפה לאמנות, אלא מתוך ייאוש קיומי:

אם אי־אפשר לשכוח, אפשר לכתוב.

כל מילה שהוא כותב נושאת בתוכה את המתח הבלתי פתיר בין הישרדות לזיכרון. הכתיבה עצמה היא עדות לאדם שחי למרות המילים.

השיבה לבוכנוואלד

לאורך הכתיבה או החיים, סמפרון מתמודד עם תחושת ניכור מתמשכת. השאלות שמלוות אותו אינן שאלות שניתן לברוח מהן. השיבה לבוכנוואלד איננה רק חזרה פיזית למקום, אלא סגירת מעגל פנימית. הוא מסכים לשוב כדי להביט שוב בצל המוות; לא כאדם שמבקש לסגור את העבר, אלא להבין את עצמו ואת מקור קיומו.

הוא חוזר אל אותו החלק בתוכו שמעולם לא עזב את המחנה.

המסע הזה איננו מסע של גאולה. זו שיבה כפולה: פיזית ואקזיסטנציאלית. אין כאן ‘לידה מחדש’. יש רק הכרה מפוכחת: שאין חיים מחוץ לזיכרון, ואין זיכרון שאיננו פוצע את החיים.

הוא שב לשם מתוך אחריות: לשוב ולראות, לשוב ולכתוב, לשוב ולשאת את השתיקה בשם השפה שנשברה, בשם הזוועה, בשם המתים, ולמען הדורות הבאים.

בוכנוואלד איננה עוד מקום; היא הפכה לצורת תודעה.

היא נוכחת בכל משפט שהוא כותב, בכל נשימה שבה הוא מנסה לחיות.

הוא כותב לא כדי להחיות את המתים, אלא כדי לא לאבד את האנושיות שנשארה בין השורות.

בסיום הספר מתברר כי הכתיבה או החיים איננו ספר על השואה בלבד, אלא על הישרדותה של התודעה בעולם שחייו ממשיכים למרות הזוועה, על חורבות המשמעות.

הכתיבה איננה סגירת מעגל, אלא מעשה נצחי של עמידה: בין חיים למוות, בין שתיקה למילה.

הוא שרד כדי להזכיר לנו שהשתיקה היא גם היא צורה של מוות ובכל זאת, היא גם הדרך היחידה שבה אפשר לשמוע את המילים שנשרפו.

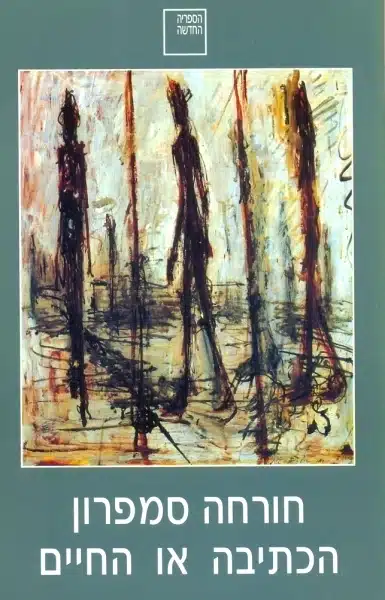

הכתיבה או החיים/ חורחה סמפרון

הוצאת הספריה החדשה, 1997, 280 עמ'

דירוג SIVI –

איכות אודיו –

Literature or Life / Jorge Semprún

Jorge Semprún did not survive the camp to live, nor to write. He survived, and for many years, he did not know why.

Literature or Life is the book in which Semprún attempts to return to that place from which he escaped—not to relive it, but to purge himself of the unbearable guilt of survival and of the moral duty to bear witness.

This is not a “memoir,” but an attempt to retrieve language from the ashes.

Semprún’s question is not what happened, but what remains of man once language itself has burned.

A native of Madrid, born into an intellectual family, a communist, a member of the Resistance, a prisoner in Buchenwald, an exile in France, a writer, screenwriter, and later Spain’s Minister of Culture, above all, he was a man forever haunted by the shadow of death.

Written forty years after liberation, the book is a collision between memory and language, between existence and aesthetics, between the need for silence and the need to speak.

The Liberation

“They cannot truly understand those three officers.

One would have to tell them about the smoke—sometimes thick and black as soot against a changing sky,

or sometimes light and gray, almost a haze, floating above the living like a ghostly premonition.

Smoke as a shroud spread across the heavens,

smoke as the last trace of friends departing—body and soul.”

On the day of liberation, nothing was clear.

The sun, absent for so long, struck Semprún’s eyes with such violence that it almost forced him to look away.

The light that followed darkness felt like a blade, not the light of Life, but the rediscovery of another kind of darkness.

For those who survived the camps, Life became a theater of death, impossible to explain or describe.

The link between sign and meaning was broken; words no longer corresponded to the world.

When the Allied soldiers arrived, the gap between what Semprún had lived and the words available to describe it struck him with full force.

How could he make them understand? How could he express horror in banal words?

The smoke became not merely a metaphor for death but a symbol of what was left:

The exhausted eyes of the survivors, searching endlessly for a single word that could contain catastrophe.

Language offers the illusion of sharing, yet each person remains imprisoned within their own experience.

“There were no living people left in that barrack.

Eyes wide open to the horror of the world,

unblinking, accusing, already extinct.

We passed through, Albert and I, throats tight, in suffocating silence.

Death unfurled his dazzling tail here, scattering icy sparks from every gaze staring into the void.”

For Semprún, liberation was not an ending but a beginning.

It was not an escape from horror, but a new confrontation with it.

His gaze was unsentimental; he sought no consolation.

Liberation was not redemption; it was a grotesque parade of survivors walking among the dead, a grim celebration where every step marked the price of survival.

The Broken Language

The passage from Life into the spectacle of death shattered Semprún not only physically and emotionally, but linguistically.

After liberation, he found himself facing a language that could no longer bear meaning.

Every bridge to the “I” had rotted. Writing became indistinguishable from flight.

“Can one imagine Heidegger’s philosophy cast into any language other than German?

Could any other tongue sustain the twisting ambiguities and pseudo-etymologies of his thought without collapsing into dust?

But did Germany itself endure the blow? Was it not struck silent—philosophically, morally—by what it had named and concealed?”

The German language, the very medium of bureaucratic annihilation, had betrayed reality.

It had collapsed morally.

How could language express being when it had already been an accomplice to destruction?

Words no longer described; they distorted.

All that survived in speech were fragments, smoldering syllables detached from the horror they once carried.

Semprún’s linguistic question is also an ethical one.

He places two centuries of German philosophy on trial.

He does not ask whether Being can still be spoken of in German, but whether any pure thought is possible after such moral collapse.

If Immanuel Kant established the conditions of knowledge, Husserl mapped the structure of consciousness, and Heidegger linked consciousness to being,

Semprún dismantles the chain altogether: what is the value of “being” when body and spirit have been erased?

What remains of consciousness when it has witnessed the unspeakable?

Fifty years after Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, which concluded:

“Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.”

Semprún answers:

“Precisely of what cannot be spoken of that one must speak.”

He writes from the knowledge that words cannot capture horror, yet insists on using them as an act of testimony, an act of survival.

Writing does not heal; it bears witness.

Every sentence is a gesture of defiance, a bridge between the living and the dead.

The act of writing is not reconciliation but farewell.

It does not mend what was broken, it sustains the space where the wound continues to breathe.

The Writing

Semprún knew that one cannot write about Buchenwald and remain alive.

This was not an insight gained later; it was instinct.

So he chose Life. Meaning: he chose silence.

For years, he did not write, did not speak, did not testify.

He lived, but through deliberate repression.

Literature or Life is not a poetic dilemma; it is the naming of the impossible.

One cannot hold both at once: writing means returning to the camp; living means forgetting.

To attempt both is to fracture beyond repair.

Primo Levi wrote to heal.

He believed that testimony could restore wholeness.

Semprún saw what became of him and refused.

He understood that actual writing would mean dying again each time he wrote.

So he remained silent, not out of fear, but as an instinct for Life.

Yet silence itself became its own form of death.

Eventually, he was forced to write not because he chose writing, but because silence had already consumed him.

His words were born not of artistic ambition, but of existential despair.

If one cannot forget, one must write.

Every word carries the impossible balance between survival and remembrance.

Writing becomes the testimony of a man who lives despite language.

The Return to Buchenwald

Throughout Literature or Life, Semprún confronts an enduring alienation.

The questions that pursue him are not those one can escape.

The return to Buchenwald is not a physical journey, but an inner reckoning.

He goes back not to close the past, but to understand himself and the source of his being.

He returns to the part of himself that never left the camp.

This is not a pilgrimage of redemption but of consciousness.

It is a double return, physical and existential.

There is no “rebirth” here, only the lucid recognition that there is no life without memory, and no memory that does not wound Life.

He goes back out of responsibility: to see again, to write again, to carry the silence in the name of language broken, of horror witnessed, of the dead remembered, and for those still to come.

Buchenwald is no longer a place; it has become a state of being.

It inhabits every line he writes, every breath he takes.

He does not write to resurrect the dead, but to preserve the human that remains between the lines.

By the end, Literature or Life is not only a book about the Holocaust, it is a meditation on the survival of consciousness itself, in a world that continues after meaning has collapsed.

Writing is not closure; it is the perpetual act of standing between Life and death, between silence and speech.

He survived to remind us that silence, too, is a form of death.

לגלות עוד מהאתר Sivi's Books

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.