Please scroll down for an English review.

כמעט אולימפוס אינו רומן אהבה.

הוא גם לא סיפור סינדרלה מודרני.

זהו רומן על עסקה.

העסקה שהעולם מציע לאישה צעירה ויפה: ביטחון תמורת ויתור על זהות.

קטיה מגיעה מקייב, עיר של עוני וחוסר יציבות, ממשפחה נשית בלבד, לאחר שהגברים נעלמו מן התמונה. אין שם אדמה יציבה ואין גבולות ברורים. ההבחנה בין מותר לאסור מטושטשת. מי ששורדת, שורדת דרך הגוף.

כשקטיה עוברת לתל אביב, לרגע נדמה שהחיים שלה עוברים תמורה.

ואדים, גבר מבוגר, עשיר, מנומס וביישן כמעט, מציע לה דירה, כסף, סדר, שקט.

הוא אינו מכה.

הוא אינו כופה.

הוא מציע. ברוך. בהיגיון. בדאגה.

אבל המחיר ברור, גם אם לא נאמר במפורש: לעזוב הכול.

אמא, סבתא, עיר, עבודה, עבר.

בסופו של דבר גם את עצמה.

זו אינה הצעת מגורים.

זו הצעת עקירה.

האולימפוס של הספר הוא לא הר

האולימפוס הוא ביתם של האלים, לא של בני־אדם.

זהו מרחב של שלמות: כוח ללא חוסר, נצח ללא זמן, סדר ללא תלות. מקום שאין בו מחלה, אין בו זקנה ואין בו צורך. בין האולימפוס לבין האנושי עובר גבול קוסמי ברור. מי שחוצה אותו אינו נענש מפני שחטא, אלא מפני שהעז.

כך במיתוס.

כך גם כאן.

איקרוס נשרף.

בלרופון הופל.

פרומתאוס נכבל.

לא משום שהיו רעים, אלא משום שחצו גבול שאסור לבני אדם לחצות.

לכן, ה״כמעט״ שבשם הספר מסמן בדיוק את הגבול הדק:

המקום שבו אדם חושב שהוא יכול להיות אל, ולומד שהוא עדיין גוף.

האולימפוס של בריינר מתגלם בדירה.

מרחב ניטרלי, שקט, לבן, כזה שיכול להתאים “לטעמם של שוכרים רבים”. אין בו זיכרון ואין בו קהילה. אין בו שכנים, עבר או הקשר. זהו מרחב סטרילי, מנותק, שמבקש למחוק את מי שנכנס אליו ולהשאיר רק פונקציה: אישה יפה שממתינה.

ואדים אינו מציע לקטיה אהבה. הוא מציע שלמות תפעולית. חיים ללא חיכוך, ללא רעש, ללא היסטוריה.

הוא מציל אותה מן הכאוס של קייב, אך גובה את המחיר במקום אחר: בדידות מוחלטת.

כך מתברר שהאולימפוס של הספר אינו יעד, אלא מכונה.

מכונה של תלות, בידוד ושחיקה איטית.

אקסנה – הגוף כפרויקט הישרדותי

מול קטיה ניצבת אקסנה.

לא כאזהרה עתידית בלבד, אלא כהווה מתמשך.

אקסנה אינה קריקטורה של “אשת אוליגרך”. היא דמות מודעת, חדה, נטולת אשליות. היא יודעת בדיוק מה היופי נתן לה, מה הוא לקח, ומה הוא עוד ייקח. אין בה נאיביות ואין בה רומנטיקה. רק חשבון קר.

היופי, עבורה, אינו מתנה. הוא הון מתכלה.

לכן הגוף שלה מנוהל כפרויקט:

הלייזר, ההזרקות, הניתוחים, המאמן הפרטי, השף. לא לשם פינוק, אלא לשם תחזוקה. לא כדי ליהנות, אלא כדי לשרוד. כל פעולה היא דחייה קטנה של פסק הדין.

הפרדוקס שקוף:

היא משקיעה הון עתק כדי להיראות כאילו לא נדרשה להשקעה כלל.

היא מבקשת להיראות טבעית, אך יודעת שטבעיות היא מותרות של צעירות.

היופי, כפי שאקסנה חיה אותו, אינו כוח חופשי. הוא מערכת משמעת. משטר יומי של שליטה, צמצום, והכחשה מתמדת של הזמן. אין בו חירות, רק הארכה.

וכשואדים בוחר בקטיה, כל המערכת הזו קורסת.

לא רק משום שבגד בה, אלא משום שהיופי המלאכותי מובס תמיד מול יופי צעיר. לא מוסרית. מבנית. ההשקעה אינה מתחרה בזמן. היא רק קונה דחייה זמנית.

אקסנה מבינה את זה.

וזו הטרגדיה האמיתית שלה.

היא אינה נופלת כי לא ידעה.

היא נופלת כי ידעה, והמשיכה בכל זאת.

במובן הזה, אקסנה אינה אנטיתזה לקטיה, אלא בבואה עתידית. שתיהן חיות בתוך אותו חוזה, רק בנקודות שונות שלו. קטיה עדיין מאמינה שאפשר להישאר שלמה בתוך העסקה. אקסנה כבר יודעת שאין דבר כזה.

קללת מידאס ההפוכה: למה בני־אדם הופכים יופי לריקבון

הלב הפילוסופי של כמעט אולימפוס אינו נמצא בסיפור האהבה, ולא אפילו בעסקה הכלכלית. הוא נמצא בשאלה מה בני־אדם עושים ליופי ברגע שהם נוגעים בו.

כאן מופיעה קללת מידאס ההפוכה.

מידאס הפך כל דבר לזהב.

בני־אדם הופכים כל דבר יפה למת.

לא מתוך רוע. מתוך חוסר יכולת לשאת שלמות.

אצל בריינר, היופי אינו מבטיח גאולה. הוא מעורר תנועה כפולה: תשוקה והרס. הרצון להחזיק בו, לשמר אותו, לקבע אותו, הוא בדיוק מה שמחסל אותו. לא מפני שיופי הוא שברירי, אלא מפני שבני־אדם הם בני תמותה. כל מגע אנושי בשלמות נושא איתו זמן, פחד, תלות וחרדה מהיעלמות.

האולימפוס מבטיח נצח.

אבל מי שנכנס אליו מביא איתו גוף.

יופי טבעי נרמס תחת ציפיות.

יופי מלאכותי מתפורר תחת מאמץ.

ובשני המקרים, הניסיון לשלוט ביופי הופך אותו לאובייקט: משהו שצריך לתחזק, למדוד, לנהל, להגן עליו מפני הזמן.

כך היופי מפסיק להיות חוויה, והופך לפרויקט.

וכשזה קורה, הוא כבר מת.

זו הסיבה שאקסנה נלחמת בזמן כמו לביאה, וזו הסיבה שקטיה נבהלת מן הגילום המוחלט של היופי. שתיהן מבינות, כל אחת בדרכה, שהשלמות אינה יעד אנושי. היא גבול. ומי שמתעקש לחצות אותו, לא נענש על חטא מוסרי, אלא על עצם היומרה.

האולימפוס של בריינר אינו מרחב אלוהי.

הוא ניסוי אנושי שנכשל.

הוא המקום שבו בני־אדם מנסים לגעת בשלמות, והופכים אותה, בעקביות, לריקבון.

באבי יאר: ההיסטוריה שאינה ניתנת למחיקה

אבל השורש העמוק של כמעט אולימפוס אינו נמצא בתל אביב. הוא נטוע בקייב. ובעוד מקום אחד שאינו מאפשר אשליות של ניקיון, סדר או התחלה מחדש: באבי יאר.

שם מתחילה שרשרת ההישרדות הנשית של הספר.

בראשיתה עומדים לודמילה ודימה, הוריה של אנה, שנרצחו בזמן מלחמת העולם השנייה. הרצח אינו רק אירוע היסטורי, אלא נקודת קיבוע: הרגע שבו הגוף הופך שוב לאובייקט, והחיים נמדדים לפי יכולת ההיעלמות. מכאן ואילך, ההישרדות אינה אידיאולוגיה, אלא טכניקה.

אנה.

ויטה.

קטיה.

שלוש נשים, שלושה דורות, ושלושה ניסיונות לשרוד בעולם שבו הגוף הוא המטבע היחיד שעובר בירושה. בכל דור מתחלפת הזירה, אך העיקרון נשאר קבוע: מי שאין לו כוח, שורד דרך הגוף. מי שאין לו יציבות, מחפש אותה בגבר. ומי שאין לו אדמה, לומד להיאחז במה שאפשר.

הגברים בספר אינם מפלצות.

הם פשוט קורסים תחת העומס.

אחד בורח לאלכוהול.

אחד בורח לכוח.

אחד בורח לכסף.

כולם נכשלים בדיוק באותו מקום: ביכולת לשאת אחריות קיומית שאינה ניתנת לפתרון באמצעות שליטה. הגוף הנשי נדרש לספוג את הקריסה הזו שוב ושוב, כפתרון זמני, כעוגן, כעסקה שקטה.

וכשקטיה מתמוטטת בדירה בתל אביב, זה אינו שבר אישי.

זהו רגע שבו כל מה שנאמר לה שאפשר למחוק, חוזר.

הטראומה אינה נעלמת.

היא רק משנה שפה.

הזעקה הפסיכוטית על “הגו גויים שנדבקו לה לעיניים ולשערות” אינה סטייה רגעית. היא החיבור הישיר בין ההיסטריה בהווה לבין האלימות ההיסטורית שמונחת מתחתיה. הגוף זוכר גם כשהתודעה מבקשת לשכוח. ההיסטוריה אינה נסגרת בפרק. היא מחליפה צורה, מחליפה דירות, מחליפה שפה, אבל אינה מתפוגגת.

במובן הזה, האולימפוס אינו רק אשליה מודרנית.

הוא ניסיון אלים למחוק היסטוריה באמצעות סדר.

והניסיון הזה נכשל, משום שאין אולימפוס שמסוגל להכיל גוף טעון בזיכרון, בזמן, ובפחד.

ואז מגיע הסיום. והוא, באמת, קיטשי. במודע

אחרי כל האלימות, הניצול, הטירוף והגוף, קטיה רוצה רק דבר אחד:

הביתה.

לא לאולימפוס.

לא לעושר.

לא ליופי.

למקום שיש בו גבול.

שבו יודעים מה מותר ומה אסור.

שבו אפשר לחלום, אבל בבוקר מתעוררים מציאות שאינה מתכחשת לעצמה.

בריינר בוחרת לסיים לא בפילוסופיה גבוהה, אלא בקשר הכי פגום והכי אנושי שיש:

האמא.

זו בחירה סנטימנטלית, כמעט פרובוקטיבית בפשטותה.

אבל היא גם הצהרה:

אחרי שכל המנגנונים הגדולים קורסים: כסף, יופי, שליטה, נשארת רק הזיקה האנושית הראשונית.

זו האמת היחידה שיכולה לנצח את האלימות האסתטית והקיומית של האולימפוס.

בסופו של דבר, זה ספר על טעות אחת יסודית.

הטעות לחשוב שאפשר לברוח מן האנושי.

מן הגוף. מן הזמן. מן הפחד. מן התלות.

האולימפוס מבטיח נצח.

אבל בני אדם נושאים מוות בכל מגע שלהם עם השלמות.

במובן הזה, “כמעט אולימפוס” אינו ספר שמעניש את הדמויות על חטא מוסרי.

הוא מעניש אותן על היומרה הקיומית להיות מעל הגבול האנושי.

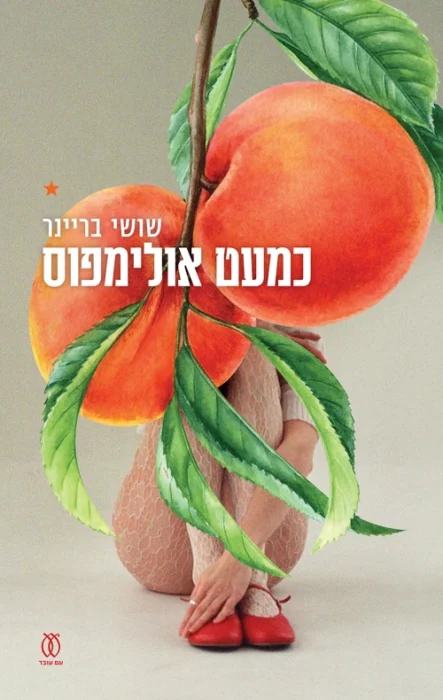

כמעט אולימפוס/ שושי בריינר

הוצאת עם עובד, 2024, 288 עמ'

דירוג SIVI –

איכות אודיו –

Practically Olympus / Shoshi Brainer: On Beauty, Money, and One Great Mistake

Practically, Olympus is not a love story.

It is not a modern Cinderella tale either.

It is a novel about a deal.

The deal the world offers a young, beautiful woman: security in exchange for the elimination of identity.

Katya arrives from Kyiv, a city of poverty, from a family of only women after the men vanished from the picture. There is no ground there and no real hold. The boundary between what is allowed and what is forbidden dissolves. Those who survive, survive through the body.

When Katya moves to Tel Aviv, it briefly seems as though her life has changed.

Vadim, an older, wealthy, polite, almost shy man, offers her an apartment, money, order, and quiet.

He does not hit.

He does not force.

He offers. Gently. Logically. With concern.

But the price is clear, even if not said aloud: to leave everything.

Mother, grandmother, city, job, past.

Ultimately, even herself.

This is not an offer of housing.

It is an offer of uprooting.

The Olympus of the novel is not a mountain

Olympus is the home of the gods, not of human beings.

It is a realm of perfection, power, and eternity—a place without lack, without dependence, without old age, and without death.

Between Olympus and humanity passes a clear cosmic boundary.

Whoever crosses it is punished. Not because they sinned, but because they dared.

Icarus burned.

Bellerophon fell.

Prometheus was chained.

Not because they were evil, but because they crossed a boundary no human is meant to cross.

Thus, the “Practically” in the title marks the thin line precisely:

The place where a human believes they can become a god, and learns they are still a body.

Brainer’s Olympus is an apartment,

neutral. Quiet. White. suitable “for many tenants’ taste.”

It holds no memory. No community. No real neighbors.

There is one beautiful woman inside, waiting.

Vadim rescues Katya from the chaos of Kyiv, but imprisons her in a golden cage.

Her existential security is purchased at the cost of absolute isolation.

And here it becomes clear that Olympus in this novel is not a destination.

It is a machine of dependence, isolation, and erosion.

Opposite Katya stands Oksana, the woman who has lived inside that cage for years.

Oksana is not a caricature of “an oligarch’s wife.” She is a tragic figure, painfully aware of her status. She knows what beauty gives, what it drains, the power it holds, and the cruelty within it. She also knows beauty is not eternal. Therefore, she cultivates it with brutal discipline.

Laser treatments, injections, surgeries, a personal trainer, and a chef.

The body is a continuous project.

Not for indulgence. For survival.

And the paradox is transparent as glass:

She spends a fortune to look as if she had spent nothing.

She wants to appear beautiful, but not as one who needs money to be beautiful.

When Vadim chooses Katya, the entire enterprise collapses.

Not only because he betrayed her.

But because artificial beauty is always defeated by natural, young beauty.

Investment never conquers time. It only delays the verdict.

The Reverse Midas Curse: Why Humans Turn Beauty into Decay

The philosophical heart of Practically Olympus lies in the dialogue between Katya and Ida.

Ida, with her porcelain, serves as the high priestess of Flemish Vanitas: everything is beautiful, everything gleams, and within it all hides a skull.

She tells Katya: Beauty decays. That is its nature.

It is not a curse of the gods.

It is a curse of humans.

The reverse Midas curse.

Midas turned everything into gold.

Humans turn everything beautiful into death.

Not intentionally. By virtue of being mortal.

Olympus, in Brainer’s novel, is not a realm of divinity, but a space in which humans attempt to touch perfection, and the human touch itself is what destroys it.

Artificial beauty crumbles under effort.

Natural beauty is trampled under expectation.

That is why Katya recoils from the absolute embodiment of beauty.

That is why Oksana fights time like a lioness.

And that is why Vadim is shattered when he asks, “What have we done?”

Humans cannot bear perfection.

They dismantle it.

They turn it into decay.

And when Katya smashes the apartment in Tel Aviv, it is not a tantrum.

It is the metaphysical declaration of the novel:

The engineered illusion of order shatters beneath a reality that rejects design.

Chaos, trauma, history, and the body prevail.

The apartment is a miniature Olympus, artificial and brittle.

Katya’s collapse is the earthquake that restores Olympus to its natural scale:

A space human beings are not built to inhabit over time.

But the true root of the novel does not lie in Tel Aviv. It lies in Kyiv. And in one more place: Babi Yar.

Katya’s family history is embedded in historical violence, racism, and genocide.

At the beginning stands the story of Ludmila and Dima, Anna’s parents, who were murdered during the Second World War.

From there, a female chain of survival begins: Anna, Vita, Katya.

In every generation, the male figure changes, but the principle remains the same: the body becomes a passing bill of exchange.

The men in the novel are not monsters.

They cannot bear the weight placed upon them by life and by the women who depend on them.

They collapse while carrying existential responsibility: one into alcohol, one into power, one into money.

And when Katya collapses in the Tel Aviv apartment, it is not only a personal breakdown.

It is the moment when everything she was told could be erased.

She reenacts Vita’s attempt to save herself through one man.

Thus, it becomes clear that the attempt to find stability in “small lives” fails just as wholly as the attempt to see it in “grand lives.”

The principle does not change—only the stage.

Her psychotic cry about the “goyim clinging to her eyes and hair” connects the hysteria of the present to the historical trauma of the family.

The past is not erased.

It merely changes form.

Then comes the ending. And it is, indeed, kitsch. Deliberately so.

After all the violence, exploitation, madness, and the body, Katya wants only one thing:

Home.

Not Olympus.

Not wealth.

Not beauty.

A place with a boundary.

Where one knows what is permitted and what is forbidden.

Where one can dream, yet wake into a reality that does not deny itself.

Brainer chooses to end not with lofty philosophy, but with the most flawed and most human bond there is:

The mother.

It is a sentimental choice, almost provocatively simple.

But it is also a declaration:

After all the great mechanisms collapse, money, beauty, and control, only the primal human bond remains.

This is the only truth strong enough to confront the aesthetic and existential violence of Olympus.

Ultimately, this is a novel about one fundamental mistake.

The mistake of believing one can escape the human.

The body. Time. Fear. Dependence.

Olympus promises eternity.

But human beings carry death into every touch of perfection.

In that sense, Practically Olympus does not punish its characters for a moral sin.

It punishes them for the existential arrogance of trying to rise above the human boundary.

לגלות עוד מהאתר Sivi's Books

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.