For English review, please scroll down.

הגעתי אל ויפה היתה שעה אחת קודם בלי יראת הכבוד.

לא כי אני מחפשת “להפיל”, אלא כי כבר שנים ברור לי שברדוגו איננו כוס התה שלי, והספר הזה רק מחדד את זה.

“ויפה היתה שעה אחת קודם” נכנס בדיוק אל תוך הקרע הזה, ספר שמעמדו נקבע מראש, אבל הקריאה בו מותירה תחושת ריק, עייפות, ואפילו כעס.

הבעיה של הספר הזה איננה עלילתית. להפך, הרעיון האנושי חזק. שָׂרִי, אישה שחייה מתנהלים בתוך כאב גופני, חרדה קהילתית, זיכרון לאומי טעון, ובדידות רגשית, היא דמות שיכולה הייתה לשאת רומן עצום.

הפרבר הירוק, הבורגנות המדושנת, האדישות שמתחזה להגנה, הרקע של כהנא, האינתיפאדה, האמירות שנטמעות בילדות מבלי להבין את משמעותן, כל אלה חומרים טעונים, נפיצים, ישראליים עד העצם. ברמת הרעיון, זה חומר זהב. ברמת החוויה, זה מכבש לשוני.

מאז 2017 פרסם סמי ברדוגו ארבעה ספרים. ארבעה. כל אחד מהם היה מועמד לפרס ספיר, ואחד אף זכה. בנקודה הזו עולה שאלה שאין דרך לעקוף אותה בנימוס: האם אנחנו עדים לגדוּלה ספרותית מתמשכת, או למערכת שהתאהבה בסגנון עד כדי אובדן שיפוט.

ברדוגו כותב מתוך תשוקה לשפה גבוהה, דחוסה, מתפתלת, כזו שמבקשת להיות גם מוזיקה וגם מטפיזיקה. הבעיה איננה עצם הבחירה, אלא שיגעון לשליטה שיצא משליטה. הוא מעמיס על כל רגע שפה מתפקעת מעצמה. שום דבר לא נאמר בפשטות. שום תחושה לא ניתנת כפי שהיא. הכול מסונן דרך מנגנון לשוני שמבקש להיות “גדול”.

יש קו דק בין הרמוניה למונוטוניה. לפעמים נדמה לנו שנגינה על מיתר אחד היא עומק, כשהיא למעשה חזרתיות. כאן הקו הזה נחצה. אותה תנועה תחבירית, אותה נשימה מקוטעת, אותו עיבוי רגשי מלאכותי.

הצליל מתענג על עצמו, עד שהקורא חדל להקשיב למשמעות. במקום תנועה רגשית נוצר רעש. במקום התקדמות נוצר סחרור במקום.

זהו הכשל המרכזי של הספר: השפה לא מעמיקה את הרגש. היא מחליפה אותו. במקום לפגוש את הפחד של שָׂרִי, את הכאב, את האשמה, הקורא פוגש את היכולות התחביריות של ברדוגו. במקום חמלה נוצרת ידענות. במקום אינטימיות נוצרת תודעה של מופע. זו פומפוזיות לא כעלבון, אלא כתיאור מדויק של יחס לא פרופורציונלי בין סגנון לחומר אנושי חי.

גם המקום שבו ברדוגו מבקש לגעת בכשל המוסרי עושה זאת בעוצמה רעיונית אך בכשל חווייתי. שָׂרִי גדלה בתוך מערכת אמירות על ערבים, על פחד, על סכין בגב, על אויב מופשט. היא לומדת לא לשנוא באמת, אלא לא להרגיש. האדישות הזו היא הכשל המוסרי האמיתי של התודעה, כלפי הקורבן המקומי בשכונה וכלפי המציאות הלאומית כולה. אבל מרוב עומס לשוני, התובנה הזו נחנקת. היא קיימת כרעיון. היא כמעט ואינה נחווית כרגש.

נקודת השבר הגדולה של הספר מגיעה בפנטזיה המינית, אותה סצנה שאמורה לשאת על גבה את המהלך החתרני כולו. ברדוגו מבקש להפוך את הגוף לזירה של תיקון, למקום שבו הלאומיות, הפחד, הזהות והעקרות האישית מתנגשים ומקבלים פתרון דרך מעשה קיצוני. ברמת הרעיון, זה מהלך רדיקלי. ברמת המימוש, זה כשל מוסרי של אופן הייצוג. התיאור חוצה את גבולות האינטימיות לא כדי לשרת את האמת של הדמות, אלא כדי לשרת את הצהרת הכוח של הכותב. במקום כאב נבנה ייצוג. במקום שבר נבנה מנגנון. הקורא לא חווה אמת כואבת, הוא מרגיש שמפעילים עליו רעיון בכוח. התחושה איננה טלטלה מוסרית, אלא ניצול אסתטי.

זה הרגע שבו הספרות מפסיקה להיות ביקורת של המציאות והופכת להיות צרכנית של הסבל שהסופר יצר בעצמו.

כאן בדיוק מתחדדת ההשוואה לאילנה ברנשטיין, שגם היא שוב מועמדת. לא כהשוואה ערכית, אלא כסימפטומים שונים של אותה מחלה ספרותית. גם אצלה השפה מגיעה לפני האדם, רק מהכיוון ההפוך. ברנשטיין שוברת את הקורא במבנים ריקים של שפה. ברדוגו חונק את הקורא בשפה מנופחת עד חנק.

שניהם מותירים את הקורא בלי אחיזה רגשית יציבה. זהו אחד הכשלים העמוקים של הפרוזה העברית העכשווית, לא חוסר כישרון, אלא עודף מודעות עצמית.

ואז מגיע הסיום. ההתערבות הישירה של ברדוגו בסיום, בפנייה הישירה אל שָׂרִי, חותמת באופן כמעט טראגי את הכשל של הרומן כולו. במקום שהדמות תנוע, הוא מסובב אותה במקום. זה סיום שמבקש להיות מטהר, אבל בפועל מחזיר את הקורא לאותו המקום. זהו, רגע שבו הסופר מפסיק להאמין בדמות ובעלילה ומחליף אותם בקולו.

הסיום הזה הוא משל לספר כולו, הרבה מהירות, הרבה רעש, מעט מאוד תזוזה נפשית. התאריך החותם את הספר איננו עיגון, אלא חתימת בעלות. אני קובע שפה זה נסגר.

ויפה הייתה שעה אחת קודם הוא רומן עם כוונות גדולות. עם רעיונות חברתיים, מודעות פוליטית ותעוזה תמאטית. אבל זהו ספר שמבקש להיות גדול מן החיים ושוכח להיות נאמן לאדם שבתוכם. השפה גדולה מהאדם, הרעיון גדול מהכאב. ובסיום, כל התחכום שבעולם כבר לא מציל את הספר מעייפות, מניכור ומהתחושה החזקה שהוא עסוק בעצמו הרבה יותר משהוא עסוק במי שהוא מתיימר להציל.

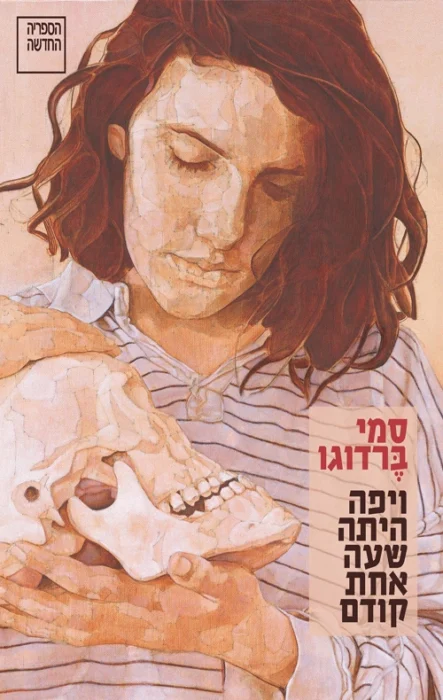

ויפה היתה שעה אחת קודם/ סמי ברדוגו

הוצאת הספריה החדשה, 2025, 279 עמ'

דירוג SIVI –

איכות אודיו –

And beautiful was the hour that came sooner

Not because I seek to “take someone down,” but because for years it has been clear to me that Bardugo is not my cup of tea, and this novel only sharpens that realization.

Since 2017, Sami Bardugo has published four novels. Four. Every single one was shortlisted for the Sapir Prize, and one of them even won. At this point, a question arises that cannot be sidestepped politely: are we witnessing sustained literary greatness, or a literary system that has fallen in love with a particular style to the point of losing its critical judgment?

And beautiful was the hour that came sooner, which enters precisely into this fracture. A novel whose status was determined in advance, yet the act of reading it leaves behind a sense of emptiness, fatigue, and even anger.

The problem with this novel is not its plot. On the contrary, the human premise is strong. Sari, a woman whose life unfolds within bodily pain, communal anxiety, a charged national memory, and emotional loneliness, is a character who could have carried a monumental novel.

The green suburb, the well-fed bourgeoisie, indifference disguised as protection, the background of Kahane, the Intifada, the phrases absorbed in childhood without understanding their meaning, all of these are volatile, explosive, deeply Israeli materials. On the level of ideas, this is pure gold. On the level of experience, it becomes a linguistic steamroller.

Bardugo writes מתוך a passion for elevated, dense, winding language, a language that seeks to be both music and metaphysics. The problem is not the choice itself, but a madness of control that spirals out of control. He overloads every moment with language that swells to the point of rupture. Nothing is said. No emotion is allowed to exist as it is. Everything is filtered through a linguistic mechanism that insists on being “great.”

There is a skinny line between harmony and monotony. At times, we confuse playing a single string repeatedly with depth, when in fact it is repetition. Here, that line is crossed—the same syntactic movement, the same broken breathing, the same artificial emotional thickening.

The sound indulges itself until the reader stops listening for meaning. Instead of emotional movement, noise is created. Instead of progress, a vortex is in place.

This is the novel’s central failure: the language does not deepen emotion; it replaces it. Instead of encountering Sari’s fear, her pain, her guilt, the reader encounters Bardugo’s syntactic virtuosity. Instead of compassion, cleverness takes over. Instead of intimacy, a sense of performance arises. This is pomposity, not as an insult, but as an accurate description of the disproportion between stylistic excess and human material.

Even where Bardugo seeks to touch on moral failure, he does so with conceptual force but experiential collapse. Sari grows up surrounded by statements about Arabs, about fear, about knives in the back, about an abstract enemy. She does not truly learn to hate. She knows not to feel. This indifference, which is the character's actual moral failure toward both the local victim in her neighborhood and the national reality as a whole, is a profound insight. But under the weight of linguistic overload, the insight suffocates. It exists as an idea. It is barely experienced as emotion.

The novel’s central breaking point arrives with the sexual fantasy, the scene meant to carry the entire subversive move on its back. Bardugo seeks to turn the body into a site of repair, a place where nationality, fear, identity, and personal barrenness collide and find resolution through an extreme act. On the level of ideas, this is a radical move. On the level of execution, it is a severe moral failure.

The description crosses the boundaries of intimacy not to serve the truth of the character, but to serve the author’s declaration of power. Instead of pain, representation is constructed. Instead of rupture, a mechanism. The reader does not experience a painful truth; instead, they feel a concept is being forced upon them. The result is not a moral shock, but aesthetic exploitation.

This is the moment where literature ceases to be a critique of reality and becomes a consumer of the suffering the author himself has produced.

Here, the comparison with Ilana Bernstein sharpens: she, too, appears again on prize lists, and with her as well, language precedes the human being, only from the opposite direction. Bernstein breaks the reader with empty linguistic structures. Bardugo suffocates the reader with inflated language.

Both leave the reader without a stable emotional anchor. This is one of the deeper failures of contemporary Hebrew prose. Not a lack of talent, but an excess of self-awareness.

And then comes the ending. Bardugo’s direct intervention at the end, his direct address to Sari, seals almost tragically the failure of the entire novel. Instead of letting the character move, he spins her in place. It is an ending that seeks to be purifying, but in practice returns the reader to the very same point. It is the moment where the author stops trusting the character and the narrative, and replaces them with his own voice.

This ending becomes a parable for the book as a whole: a great deal of speed, a great deal of noise, and minimal inner transformation. The date that seals the novel is not an anchoring gesture, but a signature of ownership. I decide where this closes.

And beautiful was the hour that came sooner, is a novel of grand intentions. It holds social ideas, political awareness, and thematic daring.

But it is a book that seeks to be larger than life and forgets to remain faithful to the human beings inside it. The language is larger than the person. The idea is larger than the pain. And in the end, all the sophistication in the world cannot rescue the novel from exhaustion, from alienation, and from the powerful sense that it is far more occupied with itself than with those it claims to save.

לגלות עוד מהאתר Sivi's Books

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

אינני מחבב ביותר טקסטים, שניכר בהם כי נועדו לתת לקוראי ספרות מקצועיים חומר לעבודה, ולא נועדו להעניק חווייה אסתטית לקורא החובבן. הגעתי סוף סוף את "מים נושקים למים" של סמי מיכאל, ששפת כתיבתו מרהיבה עין ביופיה, ועדיין היא מאפשרת הנאה פשוטה מעלילת הרומן.

לטעמי, יש הבדל תהומי בין סמי מיכאל, שאמפתי לקורא ומייצר חווית קריאה לבין סמי ברדוגו, שנראה לי שמתייחס לקורא כרע הכרחי…